Richard Burgin on his professional postcard during his early career as concertmaster and virtuoso in Russia and Scandanavia.

Chapter Five:

THE FINNISH CONNECTION

THE FINNISH CONNECTION

And wanly dove-gray-bluish eyes

Similar to Finnish skies.

Similar to Finnish skies.

—Baratynsky

I.

A year went by, nineteen eleven,

And Richard spent it rather well:

His life was hardly seventh heaven

But neither had it been the hell

Predicted by the black depression

That followed Henriette’s confession

Of friendly feelings she was sure

Would cast a pall on her allure.

But then, how often our predictions,

Our efforts to control our fate,

Do not, in fact, anticipate

The unexpected contradictions

That actual living holds in store

And no one can predict before.

And Richard spent it rather well:

His life was hardly seventh heaven

But neither had it been the hell

Predicted by the black depression

That followed Henriette’s confession

Of friendly feelings she was sure

Would cast a pall on her allure.

But then, how often our predictions,

Our efforts to control our fate,

Do not, in fact, anticipate

The unexpected contradictions

That actual living holds in store

And no one can predict before.

II.

Thus, Henriette thought her appointment

Would only make relations worse,

And Richard feared his disappointment

Betokened that his love was cursed.

Yet, in the end, their being together

Did not exacerbate the weather

But actually dispelled the gloom

That previously had forecast doom.

At first a certain discomposure

Was evident, their talk was strained,

But in a while they regained,

Because of mutual exposure,

The ease of shared experience

And overcame their reticence.

Would only make relations worse,

And Richard feared his disappointment

Betokened that his love was cursed.

Yet, in the end, their being together

Did not exacerbate the weather

But actually dispelled the gloom

That previously had forecast doom.

At first a certain discomposure

Was evident, their talk was strained,

But in a while they regained,

Because of mutual exposure,

The ease of shared experience

And overcame their reticence.

III.

The year had also had attractions

Within the realm professional

That counter-pointed the distractions

Of disengagements personal.

My Richard’s life became so busy,

It left him feeling slightly dizzy,

But work’s harmonious resonance

Drowned out romantic dissonance.

In March, still feeling in the pits, he

Received the opportunity

Of playing Scriabin’s Symphony

Of Fire under Koussevitzky* –

It was the Petersburg premiere,

And greatly brightened his despair.

Within the realm professional

That counter-pointed the distractions

Of disengagements personal.

My Richard’s life became so busy,

It left him feeling slightly dizzy,

But work’s harmonious resonance

Drowned out romantic dissonance.

In March, still feeling in the pits, he

Received the opportunity

Of playing Scriabin’s Symphony

Of Fire under Koussevitzky* –

It was the Petersburg premiere,

And greatly brightened his despair.

IV.

The summer brought a separation

From Henriette which made him glum,

But as a kind of reparation

His work in Riga was a plum:

His solos with the Philharmonic

Of Warsaw was a potent tonic,

And though they left him quite fatigued,

They guaranteed he had “big-leagued”

And gave him little time to ponder

How much he missed his Henriette,

How much his heart could not forget,

And just how much it had grown fonder.

To be so tired one can’t think,

Surpasses not to sleep a wink.

From Henriette which made him glum,

But as a kind of reparation

His work in Riga was a plum:

His solos with the Philharmonic

Of Warsaw was a potent tonic,

And though they left him quite fatigued,

They guaranteed he had “big-leagued”

And gave him little time to ponder

How much he missed his Henriette,

How much his heart could not forget,

And just how much it had grown fonder.

To be so tired one can’t think,

Surpasses not to sleep a wink.

V.

He had returned to school assuming

They would continue as before –

As friends and colleagues, just resuming

Their work together, nothing more.

Yet while their everyday relations

Remained the same, in conversations

Her manner seemed … more indirect.

On matters where he would expect

Straightforwardness, she played the hinter.

At first he hardly was aware

Of her far more elusive air,

But as the fall passed into winter,

He sensed there really was a change –

In fact, she acted downright strange.

They would continue as before –

As friends and colleagues, just resuming

Their work together, nothing more.

Yet while their everyday relations

Remained the same, in conversations

Her manner seemed … more indirect.

On matters where he would expect

Straightforwardness, she played the hinter.

At first he hardly was aware

Of her far more elusive air,

But as the fall passed into winter,

He sensed there really was a change –

In fact, she acted downright strange.

VI.

Before, she’d never been offended,

But now she often acted hurt;

Before, she never had pretended,

But now she openly would flirt.

Where formerly she’d been judicious,

She now at times became capricious

And would occasionally employ

Devices positively coy.

Where once she’d been enthusiastic

And joined in group activity,

She now avoided company,

Retreated to a life monastic

And never let the truth be known

Why she preferred to be alone.

But now she often acted hurt;

Before, she never had pretended,

But now she openly would flirt.

Where formerly she’d been judicious,

She now at times became capricious

And would occasionally employ

Devices positively coy.

Where once she’d been enthusiastic

And joined in group activity,

She now avoided company,

Retreated to a life monastic

And never let the truth be known

Why she preferred to be alone.

VII.

One needs but scant sophistication

To realize what these changes show,

But Richard lacked an education

In sentiment and did not know.

Her coyness made him feel unsettled.

By her caprices he was nettled

And pushed to pleading self-defense

For words not meant to cause offense.

He found her presence most perturbing

And wished at times she’d go away,

But if she did, in just one day

He found her absence more disturbing!

He had no clue to what it meant …

(Oh reader, he was innocent.)

To realize what these changes show,

But Richard lacked an education

In sentiment and did not know.

Her coyness made him feel unsettled.

By her caprices he was nettled

And pushed to pleading self-defense

For words not meant to cause offense.

He found her presence most perturbing

And wished at times she’d go away,

But if she did, in just one day

He found her absence more disturbing!

He had no clue to what it meant …

(Oh reader, he was innocent.)

VIII.

Thus, not without some consternation,

My Richard greeted nineteen twelve,

And looked ahead. His graduation

In May loomed large: he had to shelve

His private worries since despairing

Was not conducive to preparing

For his profession’s future chores,

His first real job, in Helsingfors.

(My goodness! I forgot to mention

The most important thing of all

Last summer brought – a job next fall.

Please forgive my inattention –

It must have been one of the times

When facts of life eluded rhymes.)

My Richard greeted nineteen twelve,

And looked ahead. His graduation

In May loomed large: he had to shelve

His private worries since despairing

Was not conducive to preparing

For his profession’s future chores,

His first real job, in Helsingfors.

(My goodness! I forgot to mention

The most important thing of all

Last summer brought – a job next fall.

Please forgive my inattention –

It must have been one of the times

When facts of life eluded rhymes.)

IX.

But I shall spare you long reflections

On why my memory mis-fared

And turn to Burgin’s recollections

Of nineteen twelve when he prepared

To make the imminent transition

To his new Helsingfors position.

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

On why my memory mis-fared

And turn to Burgin’s recollections

Of nineteen twelve when he prepared

To make the imminent transition

To his new Helsingfors position.

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

X.

“And my philosophy, I remember,

When going to a foreign land,

Was wanting to become a member

Of that new culture, understand

The language and the literary

Traditions. Literature was very

Important, interesting for me.

I also tended, musically,

Perhaps because I’d lived in Prussia

When I was young, you know, Berlin,

To be more cosmopolitan.

I sort of went outside of Russia,

You know, to find composers who

Were different from the ones we knew.

When going to a foreign land,

Was wanting to become a member

Of that new culture, understand

The language and the literary

Traditions. Literature was very

Important, interesting for me.

I also tended, musically,

Perhaps because I’d lived in Prussia

When I was young, you know, Berlin,

To be more cosmopolitan.

I sort of went outside of Russia,

You know, to find composers who

Were different from the ones we knew.

XI.

“So when I knew that it was certain

I’d go to Finland, I found out

About Sibelius’s Concerto,

Which only then, I learned about.

I practiced that and then I brought it

To class. And Auer’d never taught it.

Though Tseitlin* played it – that he knew –

For him it was completely new.

And also Sinding, for example –

I brought to class and played his Third

Concerto which no one had heard,

And Auer, since he liked to sample

New music, had respect for me,

That I would bring it in, you see.

I’d go to Finland, I found out

About Sibelius’s Concerto,

Which only then, I learned about.

I practiced that and then I brought it

To class. And Auer’d never taught it.

Though Tseitlin* played it – that he knew –

For him it was completely new.

And also Sinding, for example –

I brought to class and played his Third

Concerto which no one had heard,

And Auer, since he liked to sample

New music, had respect for me,

That I would bring it in, you see.

XII.

“And also, when I went to Finland

I learned – not Finnish actually –

But Swedish since there were in Finland

Still Swedish-speaking Finns, you see.

That was the strangest situation –

A city with a population

That was comparatively small,

A hundred fifty thousand in all,

And in a country of three million

That also, isn’t very large,

They had two symphony orchestras,

And each one gave a concert season.

No day would pass, in other words,

Without a concert in Helsingfors.

I learned – not Finnish actually –

But Swedish since there were in Finland

Still Swedish-speaking Finns, you see.

That was the strangest situation –

A city with a population

That was comparatively small,

A hundred fifty thousand in all,

And in a country of three million

That also, isn’t very large,

They had two symphony orchestras,

And each one gave a concert season.

No day would pass, in other words,

Without a concert in Helsingfors.

XIII.

“Those two full orchestras reflected

The country’s ethnic rivalries:

The one that Kajanus* directed

Had nationalistic tendencies;

The one I was associated

With, Schnéevoigt’s* (educated

In Germany although a Finn)

Was more inclined towards Berlin.

But due to this great competition,

Those special Finnish politics,

Helsinki music life was rich,

And Finland’s musical position

Was really way ahead, I’d say,

Of any country’s of its day.”

The country’s ethnic rivalries:

The one that Kajanus* directed

Had nationalistic tendencies;

The one I was associated

With, Schnéevoigt’s* (educated

In Germany although a Finn)

Was more inclined towards Berlin.

But due to this great competition,

Those special Finnish politics,

Helsinki music life was rich,

And Finland’s musical position

Was really way ahead, I’d say,

Of any country’s of its day.”

XIV.

I’ve quoted Burgin’s recollections,

His look behind, to look ahead

And show the various connections

To which his education led,

But in the meantime I’ve left pending

A situation far more rending

Than my young violinist’s art –

The future of his tortured heart.

So now I’ll do my own backtracking,

Pick up the still unwoven strand

I dropped with Richard, nothing planned,

Uncomprehendingly a-lacking,

A-lassing, angered and upset

About the change in Henriette.

His look behind, to look ahead

And show the various connections

To which his education led,

But in the meantime I’ve left pending

A situation far more rending

Than my young violinist’s art –

The future of his tortured heart.

So now I’ll do my own backtracking,

Pick up the still unwoven strand

I dropped with Richard, nothing planned,

Uncomprehendingly a-lacking,

A-lassing, angered and upset

About the change in Henriette.

XV.

Her oddities did not diminish

But just grew odder in the spring,

And Richard saw his future Finnish

As finishing their future thing.

Again, the clouds of disillusion,

Annoyance and irresolution

Were gathering and seemed to blight

Professional horizons bright.

He tried to talk but met resistance:

Whenever he would ask, “What’s wrong?”

She’d say, “I’ve got to go, so long.”

And pleading proved of no assistance:

To his, “Oh please don’t make a scene,”

She’d shrug, “I don’t know what you mean?!”

But just grew odder in the spring,

And Richard saw his future Finnish

As finishing their future thing.

Again, the clouds of disillusion,

Annoyance and irresolution

Were gathering and seemed to blight

Professional horizons bright.

He tried to talk but met resistance:

Whenever he would ask, “What’s wrong?”

She’d say, “I’ve got to go, so long.”

And pleading proved of no assistance:

To his, “Oh please don’t make a scene,”

She’d shrug, “I don’t know what you mean?!”

XVI.

And yet, the more she drove him crazy,

The more, it seemed, he found her dear;

The more she left the future hazy,

The more he wished to make it clear.

At last, one night when he was pondering

Her oddities, he started wondering,

‘What can I do? What should I say?

There simply has to be some way,

Some instrument at my disposal,

To solve this problem … Let me see …

Perhaps I’ll make her … [suddenly,

The answer sounded] … a proposal!

That’s it! If she says yes, it’s great;

If no, well, still I’ll know my fate.’

The more, it seemed, he found her dear;

The more she left the future hazy,

The more he wished to make it clear.

At last, one night when he was pondering

Her oddities, he started wondering,

‘What can I do? What should I say?

There simply has to be some way,

Some instrument at my disposal,

To solve this problem … Let me see …

Perhaps I’ll make her … [suddenly,

The answer sounded] … a proposal!

That’s it! If she says yes, it’s great;

If no, well, still I’ll know my fate.’

XVII.

Dear reader, I shall skip the details

Of his proposal. Why rehash

The sort of banal scene that retails

In Harlequins for petty cash?

He made it after graduation

And common to the situation

His eyes expressed both hope and dread,

He mumbled and his face was red.

She also blushed, demure, elated

To hear him get it out at last,

Then sighed and whispered, breathing fast,

Her answer, which you have awaited

For thirteen lines, but now must guess:

One word to rhyme my couplet: ____.

Of his proposal. Why rehash

The sort of banal scene that retails

In Harlequins for petty cash?

He made it after graduation

And common to the situation

His eyes expressed both hope and dread,

He mumbled and his face was red.

She also blushed, demure, elated

To hear him get it out at last,

Then sighed and whispered, breathing fast,

Her answer, which you have awaited

For thirteen lines, but now must guess:

One word to rhyme my couplet: ____.

XVIII.

Nor will you hear from me effusions

About my lovers’ happiness.

With all such blissful grand illusions

My Muse does not have much success.

She finds it telling that for happy

The most convenient rhyme is sappy;

It bores her that in English, kiss,

So glibly harmonizes bliss.

‘In Russian, kiss is more amusing,’

She grinned, ‘what rhymes with potselui?’

‘Well what?’ ‘You know,’ she whispered, ‘____.’

(Forgive me, reader, for refusing

To write a word so crass and sick

It makes my conscience feel a prick.)

About my lovers’ happiness.

With all such blissful grand illusions

My Muse does not have much success.

She finds it telling that for happy

The most convenient rhyme is sappy;

It bores her that in English, kiss,

So glibly harmonizes bliss.

‘In Russian, kiss is more amusing,’

She grinned, ‘what rhymes with potselui?’

‘Well what?’ ‘You know,’ she whispered, ‘____.’

(Forgive me, reader, for refusing

To write a word so crass and sick

It makes my conscience feel a prick.)

XIX.

But onward! What’s the greatest hurdle

My youthful lovers have to face?

What can make their hot blood curdle

With thoughts of scandal, shame, disgrace?

What wear-and-tear can snap the suture

With which they have sewn up their future?

What worry turns them into wrecks?

No, no, you’re wrong, it isn’t sex.

No, please don’t think I’m being funny,

It isn’t that, or their rapport,

Nor problems of the mundane sort

Like housing, jobs, or even money.

There’s something worse than all of these –

Their meetings with their families.

My youthful lovers have to face?

What can make their hot blood curdle

With thoughts of scandal, shame, disgrace?

What wear-and-tear can snap the suture

With which they have sewn up their future?

What worry turns them into wrecks?

No, no, you’re wrong, it isn’t sex.

No, please don’t think I’m being funny,

It isn’t that, or their rapport,

Nor problems of the mundane sort

Like housing, jobs, or even money.

There’s something worse than all of these –

Their meetings with their families.

XX.

Perhaps you think I’m either joking

Or have completely lost my mind,

Or feel the need to be provoking

Because I have an axe to grind –

But you are wrong. It’s not derangement

That moves me here, or some estrangement.

So let me take a little space

And I shall try to make my case …

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

Or have completely lost my mind,

Or feel the need to be provoking

Because I have an axe to grind –

But you are wrong. It’s not derangement

That moves me here, or some estrangement.

So let me take a little space

And I shall try to make my case …

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

XXI.

If I am wrong, what child would grovel?

Or wish his home another one?

If I am wrong, what kind of novel

Were ever written or begun?

What plays or films would give enjoyment?

Where would we find enough employment

For counselors, psychiatrists,

Or lawyers, priests and therapists?

If I am wrong, who’d ever bother

To read the works of Sigmund Freud?

And who would ever get annoyed

Or want to fight with his/her mother?

If I am wrong – now, don’t get sore –

All life would stop or be a bore.

Or wish his home another one?

If I am wrong, what kind of novel

Were ever written or begun?

What plays or films would give enjoyment?

Where would we find enough employment

For counselors, psychiatrists,

Or lawyers, priests and therapists?

If I am wrong, who’d ever bother

To read the works of Sigmund Freud?

And who would ever get annoyed

Or want to fight with his/her mother?

If I am wrong – now, don’t get sore –

All life would stop or be a bore.

XXII.

For all its worrisome detractions,

Its woes and tensions very real,

One’s family still has great attractions,

Potential for one’s own ideal

Of happiness. Who doesn’t pander

To that beguiling propaganda

That there exists, and yours can be

(With luck) the perfect family?

And never is this feeling stronger

Than when you’re coming home from school:

It seems your absence has been cruel,

It cannot last a moment longer,

You yearn for home, and hence your zeal

To make your visit there ideal.

Its woes and tensions very real,

One’s family still has great attractions,

Potential for one’s own ideal

Of happiness. Who doesn’t pander

To that beguiling propaganda

That there exists, and yours can be

(With luck) the perfect family?

And never is this feeling stronger

Than when you’re coming home from school:

It seems your absence has been cruel,

It cannot last a moment longer,

You yearn for home, and hence your zeal

To make your visit there ideal.

XXIII.

And what’s ideal, you ask? That question

Re families and other things

Quite frankly gives me indigestion,

And clips my Muse’s soaring wings.

We can’t give positive definitions,

But there are contexts and conditions

Where we’ll suggest what it is not:

It’s not in general what you’ve got.

In striving, it is, not desiring

What is impossible to get,

In setting up, it’s not upset;

In ending, it is, not expiring;

In blossoming, it’s not to wilt;

In family life, it is, not guilt.

Re families and other things

Quite frankly gives me indigestion,

And clips my Muse’s soaring wings.

We can’t give positive definitions,

But there are contexts and conditions

Where we’ll suggest what it is not:

It’s not in general what you’ve got.

In striving, it is, not desiring

What is impossible to get,

In setting up, it’s not upset;

In ending, it is, not expiring;

In blossoming, it’s not to wilt;

In family life, it is, not guilt.

XXIV.

Ah guilt! Who’ll offer me a reason

Why every family structure’s built,

When no one has committed treason,

On mutual do-not-blame- me silt?

Is there a way of understanding

The permanent self-reprimanding

That tips us from our cradle’s tilt

And tears to bits our comfort quilt?

Why do our most sincere laudations

To families have a guilty lilt?

Why is the Golden Rule so gilt

With burnished self-recriminations?

Why, over milk by parents spilt,

Do children burst in tears from guilt?

Why every family structure’s built,

When no one has committed treason,

On mutual do-not-blame- me silt?

Is there a way of understanding

The permanent self-reprimanding

That tips us from our cradle’s tilt

And tears to bits our comfort quilt?

Why do our most sincere laudations

To families have a guilty lilt?

Why is the Golden Rule so gilt

With burnished self-recriminations?

Why, over milk by parents spilt,

Do children burst in tears from guilt?

XXV.

Like everyone, my Richard suffered

From guilt though he was not aware

Of this since early on he’d buffered

Himself against its wear-and-tear

By showing filial devotion,

Behavior based upon the notion,

That he could best avoid complaint

By acting out the role of saint.

He’d made his parents’ mute injunction

His own: just always do your best,

Indeed, he never let it rest

And planned his future in conjunction

With what he knew they would expect,

And loved and showed them great respect.

From guilt though he was not aware

Of this since early on he’d buffered

Himself against its wear-and-tear

By showing filial devotion,

Behavior based upon the notion,

That he could best avoid complaint

By acting out the role of saint.

He’d made his parents’ mute injunction

His own: just always do your best,

Indeed, he never let it rest

And planned his future in conjunction

With what he knew they would expect,

And loved and showed them great respect.

XXVI.

The only time he could remember

When he had disappointed them

Was in that bleak New York November –

For that he did himself condemn.

But otherwise, his guilty flurries

Were hidden in what he called “worries”

That he would ever do again

What might cause his parents pain.

He felt withal he’d been successful.

Through graduation – knock on wood! –

He had done well and had been good.

Yet lately, feelings most distressful

Disturbed his generally guiltless state

Whenever he would contemplate

When he had disappointed them

Was in that bleak New York November –

For that he did himself condemn.

But otherwise, his guilty flurries

Were hidden in what he called “worries”

That he would ever do again

What might cause his parents pain.

He felt withal he’d been successful.

Through graduation – knock on wood! –

He had done well and had been good.

Yet lately, feelings most distressful

Disturbed his generally guiltless state

Whenever he would contemplate

XXVII.

His visit home. In consternation,

He tried to find the reason why,

From careful self-examination.

At first, it yielded no reply:

Indeed, what possible abrasion

Could mar this happiest occasion

Of sharing joys with kin he missed?

His being a Silver Medalist,

The job that he’d begin next season,

And then, the greatest news of all,

His plans to marry in the fall …

There seemed to be no earthly reason

Why he should be at all upset,

Unless … it might be … Henriette!

He tried to find the reason why,

From careful self-examination.

At first, it yielded no reply:

Indeed, what possible abrasion

Could mar this happiest occasion

Of sharing joys with kin he missed?

His being a Silver Medalist,

The job that he’d begin next season,

And then, the greatest news of all,

His plans to marry in the fall …

There seemed to be no earthly reason

Why he should be at all upset,

Unless … it might be … Henriette!

XXVIII.

Suddenly, the realization,

A-blush with guilt, had dawned on him,

That maybe out of sublimation,

Embarrassment, or by some whim,

Not once in person or by letter

Had he mentioned Henrietta.

So it would come as quite a shock

When he and she, engaged, would walk

Into his home … O Lord, what terror!

Oh why had he not paved the way

For bringing home his … fiancée?

And now that he had seen his error,

The happiness that lay ahead

Betokened nothing, if not dread.

A-blush with guilt, had dawned on him,

That maybe out of sublimation,

Embarrassment, or by some whim,

Not once in person or by letter

Had he mentioned Henrietta.

So it would come as quite a shock

When he and she, engaged, would walk

Into his home … O Lord, what terror!

Oh why had he not paved the way

For bringing home his … fiancée?

And now that he had seen his error,

The happiness that lay ahead

Betokened nothing, if not dread.

XXIX.

So reader, what’s your expectation?

Has Richard’s guilty prophecy

Foreseen the actual situation

He’ll meet within his family?

Or will there be a contradiction

Of his most dread and sure prediction,

More proof of that phenomenon

That I affirmed in stanza One?

In other words, what's my intention?

Will I eventually undermine,

Or have my story stay in line

With my auctorial contention?

You ought to have some time to guess,

So I shall once again digress

Has Richard’s guilty prophecy

Foreseen the actual situation

He’ll meet within his family?

Or will there be a contradiction

Of his most dread and sure prediction,

More proof of that phenomenon

That I affirmed in stanza One?

In other words, what's my intention?

Will I eventually undermine,

Or have my story stay in line

With my auctorial contention?

You ought to have some time to guess,

So I shall once again digress

XXX.

Just briefly, with some information

About the Burgin family scene

Where Richard hurried from the station

(With Henriette) on May nineteen.

You’ve met the missus and the mister,

His oldest brother and his sister,

And now I shall the others name:

In nineteen hundred Myron came,

And not too far behind him, Paula,

And then, Mateus-Teodor

And Juliusz (whom Ronia bore

Within a year of one another);

And that completes the Burgin eight

Who now await our graduate.

About the Burgin family scene

Where Richard hurried from the station

(With Henriette) on May nineteen.

You’ve met the missus and the mister,

His oldest brother and his sister,

And now I shall the others name:

In nineteen hundred Myron came,

And not too far behind him, Paula,

And then, Mateus-Teodor

And Juliusz (whom Ronia bore

Within a year of one another);

And that completes the Burgin eight

Who now await our graduate.

XXXI.

With young Bernard and more so, Lily

My Richard shared the closest ties.

They were the only siblings, really,

He’d lived with so that’s no surprise.

Though when away he wondered whether

It would seem strange to be together,

“The family was so closely knit,”[1]Comment of Maria Wierna Burgin, widow of Juliusz Burgin, made to the author in August, 1981.

He rarely felt apart from it.

He shared close ties with all his siblings

From whom by travels he’d been cleft;

Once home, he felt he’d never left

And joined into their joys and quibblings

Spontaneously and magically,

A limb re-grown upon the tree.

My Richard shared the closest ties.

They were the only siblings, really,

He’d lived with so that’s no surprise.

Though when away he wondered whether

It would seem strange to be together,

“The family was so closely knit,”[1]Comment of Maria Wierna Burgin, widow of Juliusz Burgin, made to the author in August, 1981.

He rarely felt apart from it.

He shared close ties with all his siblings

From whom by travels he’d been cleft;

Once home, he felt he’d never left

And joined into their joys and quibblings

Spontaneously and magically,

A limb re-grown upon the tree.

XXXII.

Of course, the Burgins had their troubles.

Moisey and Ronia, you recall,

Were psychologically doubles –

At once enthralled and disenthralled

With one another. Yet, they rarely

Indulged in arguments unfairly

Before the children: he would cease,

Or she would tensely hold her peace.

In nineteen twelve, I ought to mention,

Moisey’s finances had improved,

Which put him in a better mood.

Now optimistic, free from tension,

He had regained his former pluck,

His faith in self, and in his luck.

Moisey and Ronia, you recall,

Were psychologically doubles –

At once enthralled and disenthralled

With one another. Yet, they rarely

Indulged in arguments unfairly

Before the children: he would cease,

Or she would tensely hold her peace.

In nineteen twelve, I ought to mention,

Moisey’s finances had improved,

Which put him in a better mood.

Now optimistic, free from tension,

He had regained his former pluck,

His faith in self, and in his luck.

XXXIII.

And so, the home on Nowolipka[2]Nowolipka was a main street in the Jewish section of Warsaw.

When Richard crossed its threshold, rent

With guilt, krasneya, no s ulybkoi,[3]krasneya, no s ulybkoi = blushing, but with a smile (Russian).

Though not ideal, was quite content.

Arrival. Shouts of joy, embracing,

Excitement. With his pulse beat racing,

He raised his hand for silence: “Well,”

He paused, “I’ve got great news to tell!

Please meet …”. Although the unexpected

Amazed and shocked them all at first,

There was no scandalous outburst.

Moisey and Ronia both respected

The rules of hospitality,

He noisily, she silently.

When Richard crossed its threshold, rent

With guilt, krasneya, no s ulybkoi,[3]krasneya, no s ulybkoi = blushing, but with a smile (Russian).

Though not ideal, was quite content.

Arrival. Shouts of joy, embracing,

Excitement. With his pulse beat racing,

He raised his hand for silence: “Well,”

He paused, “I’ve got great news to tell!

Please meet …”. Although the unexpected

Amazed and shocked them all at first,

There was no scandalous outburst.

Moisey and Ronia both respected

The rules of hospitality,

He noisily, she silently.

XXXIV. XXXV.

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

.......................................................

XXXVI.

Two weeks had passed. The visit, nearing

Its end, had settled into calm,

My couple outwardly appearing

Well-rested and without a qualm;

But appearances can be deceiving,

And Richard found himself receiving,

Through all the noisy fun and sport,

A message of the silent sort.

For all the stories, banter, blather,

And chitchat, no one said a word

Pro eto, till one night he heard[4]Pro eto literally means, “about that.” It is a common euphemism in Russian for “about love.”

His mother whisper to his father,

“You know, Moisey, this is no whim.

You’d better have a talk with him.”

Its end, had settled into calm,

My couple outwardly appearing

Well-rested and without a qualm;

But appearances can be deceiving,

And Richard found himself receiving,

Through all the noisy fun and sport,

A message of the silent sort.

For all the stories, banter, blather,

And chitchat, no one said a word

Pro eto, till one night he heard[4]Pro eto literally means, “about that.” It is a common euphemism in Russian for “about love.”

His mother whisper to his father,

“You know, Moisey, this is no whim.

You’d better have a talk with him.”

XXXVII.

So on the eve of his departure,

Moisey and Richard took a walk

To … (oh, my reader, aren’t you smart, you’re

Quite right about the rhyme here) talk.

Around the neighborhood they ambled

As Moses nervously pre-ambled

The topic, feeling out of joint,

But finally he approached the point:

“So Richard, now you plan to marry?”

“I do. I love her very much.”

“I know, my boy, but it is such

A … serious step, a lot to carry,

I mean, responsibility … “

“I realize that.” “You won’t be free,

Moisey and Richard took a walk

To … (oh, my reader, aren’t you smart, you’re

Quite right about the rhyme here) talk.

Around the neighborhood they ambled

As Moses nervously pre-ambled

The topic, feeling out of joint,

But finally he approached the point:

“So Richard, now you plan to marry?”

“I do. I love her very much.”

“I know, my boy, but it is such

A … serious step, a lot to carry,

I mean, responsibility … “

“I realize that.” “You won’t be free,

XXXVIII.

“So free, you know. I mean, it’s harder …

A wife and … children … to support …

That’s quite a job, to keep the larder

Well-stocked,” he started to exhort,

“To make a living isn’t easy!”

“I know that but don’t be uneasy

On that score. I feel quite secure

My job in Finland will assure

Us stable income, and …” “Yes Richard,

Of course. And I’m so proud of you,

About the job … your mother, too,

But son, we [words of warning which had

Eluded him, now reached his tongue]

We feel that you are … just too young.”

A wife and … children … to support …

That’s quite a job, to keep the larder

Well-stocked,” he started to exhort,

“To make a living isn’t easy!”

“I know that but don’t be uneasy

On that score. I feel quite secure

My job in Finland will assure

Us stable income, and …” “Yes Richard,

Of course. And I’m so proud of you,

About the job … your mother, too,

But son, we [words of warning which had

Eluded him, now reached his tongue]

We feel that you are … just too young.”

XXXIX.

“I’m not, I’m not,” the youth insisted,

Too angrily to save his pride.

“We think you are,” Moisey persisted

“And maybe we’re unjustified,

Who knows? But wouldn’t it be frightful

To end your visit, so delightful,

Somehow estranged?” He turned his eyes

To Richard, “So, let’s compromise.”

“How?” “Listen, I am not opposing

Your getting married, or your choice,

In fact, it makes my heart rejoice

To see you happy. I’m proposing

You … put it off a year or two,

And then, my boy, good luck to you.”

Too angrily to save his pride.

“We think you are,” Moisey persisted

“And maybe we’re unjustified,

Who knows? But wouldn’t it be frightful

To end your visit, so delightful,

Somehow estranged?” He turned his eyes

To Richard, “So, let’s compromise.”

“How?” “Listen, I am not opposing

Your getting married, or your choice,

In fact, it makes my heart rejoice

To see you happy. I’m proposing

You … put it off a year or two,

And then, my boy, good luck to you.”

XL.

So once again my story hangs on

The guessing game of either-or,

But since I’m bored with tempos langsam,

I won’t suspend you as before.

He did agree to a postponement –

I don’t know why – perhaps atonement?

Perhaps what Ronia left unsaid?

Or guilt? Or what his father said?

But he gave in, and at this juncture,

You may be thinking Richard’s way

Will follow that of Prince Andrey.*

Such sharpness normally would puncture

My Muse, but her balloon is not

Inflated yet with such a thought.

The guessing game of either-or,

But since I’m bored with tempos langsam,

I won’t suspend you as before.

He did agree to a postponement –

I don’t know why – perhaps atonement?

Perhaps what Ronia left unsaid?

Or guilt? Or what his father said?

But he gave in, and at this juncture,

You may be thinking Richard’s way

Will follow that of Prince Andrey.*

Such sharpness normally would puncture

My Muse, but her balloon is not

Inflated yet with such a thought.

XLI.

Unlike Natasha, Henrietta –

And everything depends on HER –

Herself believed it might be better

If their marriage were deferred.

It wasn’t that she didn’t love him,

Or somehow held herself above him,

Or that she didn’t want to wed

Or that she hadn’t lost her head

Or was by nature too complacent.

She did not know quite what was wrong

Except that all the very strong

Emotions and desires, nascent

Within her sometimes strangely made

Her feel a little bit afraid.

And everything depends on HER –

Herself believed it might be better

If their marriage were deferred.

It wasn’t that she didn’t love him,

Or somehow held herself above him,

Or that she didn’t want to wed

Or that she hadn’t lost her head

Or was by nature too complacent.

She did not know quite what was wrong

Except that all the very strong

Emotions and desires, nascent

Within her sometimes strangely made

Her feel a little bit afraid.

XLII.

And this confused and frightened feeling

Welled up in her and overtook

Her love when he, with eyes appealing,

Would radiate a certain look.

It seemed to her his look was gunning

Her down, it made her feel like running,

So much at times, it was a strain

To make the effort to remain.

That look, she knew, was not a sin and

She couldn’t kill his happiness

For what she deemed her silliness,

But when she saw him off to Finland,

She sensed beneath her parting grief

An undercurrent of relief.

Welled up in her and overtook

Her love when he, with eyes appealing,

Would radiate a certain look.

It seemed to her his look was gunning

Her down, it made her feel like running,

So much at times, it was a strain

To make the effort to remain.

That look, she knew, was not a sin and

She couldn’t kill his happiness

For what she deemed her silliness,

But when she saw him off to Finland,

She sensed beneath her parting grief

An undercurrent of relief.

XLIII.

He journeyed forth, quite unaware of

The fears that plagued his darling’s soul.

He had his own portentous share of

Anxieties about his goal.

The future alternately brightened

And then grew dim and left him frightened.

Had it been right for him to choose

To put things off? Or would he lose?

A year or two – that seemed forever!

Yes, clearly he had been a fool

To let his father overrule

His own desires, and whenever

Impatient thoughts like these would nag,

It seemed that time would really drag.

The fears that plagued his darling’s soul.

He had his own portentous share of

Anxieties about his goal.

The future alternately brightened

And then grew dim and left him frightened.

Had it been right for him to choose

To put things off? Or would he lose?

A year or two – that seemed forever!

Yes, clearly he had been a fool

To let his father overrule

His own desires, and whenever

Impatient thoughts like these would nag,

It seemed that time would really drag.

XLIV.

But he became so very busy,

The weeks and months flew by so fast,

That time outstripped his private tizzy

About the year he wouldn’t last,

That somehow passed before he knew it,

Or even how he’d gotten through it.

His old time-tested rule, “Don’t shirk!”

And his devotion to his work

Not only made the time go faster,

They brought a second timely boon,

And really, not a bit too soon:

He was promoted concertmaster,[5]In 1914 the two Helsingfors orchestras merged into one, the Helsingfors City Orchestra, in which Burgin served as concertmaster until 1916.

Which he was sure would save the day

And put an end to all delay.

The weeks and months flew by so fast,

That time outstripped his private tizzy

About the year he wouldn’t last,

That somehow passed before he knew it,

Or even how he’d gotten through it.

His old time-tested rule, “Don’t shirk!”

And his devotion to his work

Not only made the time go faster,

They brought a second timely boon,

And really, not a bit too soon:

He was promoted concertmaster,[5]In 1914 the two Helsingfors orchestras merged into one, the Helsingfors City Orchestra, in which Burgin served as concertmaster until 1916.

Which he was sure would save the day

And put an end to all delay.

XLV.

And so, the Helsingfors connection,

Which Richard feared would be the death

Of his and Henriette’s affection,

Turned out to give it second breath –

At least when viewed from his perspective

Since it attained his dual objective:

Material security,

And marital felicity.

He was all smiles when he told her

And gazed enraptured in her eyes

To see the love in their surprise

And with his eyes to try and hold her,

But her response to his great news

Had left him feeling quite confused.

Which Richard feared would be the death

Of his and Henriette’s affection,

Turned out to give it second breath –

At least when viewed from his perspective

Since it attained his dual objective:

Material security,

And marital felicity.

He was all smiles when he told her

And gazed enraptured in her eyes

To see the love in their surprise

And with his eyes to try and hold her,

But her response to his great news

Had left him feeling quite confused.

XLVI.

It’s true that she had been excited,

Extremely proud and most impressed,

But asking her to marry blighted

Her mood, and she became distressed.

Her manner changed to slightly ruffled,

Her voice then sounded almost muffled,

And she appeared to hesitate

When he had tried to set the date.

Her attitude had been perplexing.

Although at last she did say yes,

The when was anybody’s guess.

Her diffidence to him was vexing –

She seemed at once to dare and daunt –

‘Good Lord,’ he mused, ‘what does she want?!’

Extremely proud and most impressed,

But asking her to marry blighted

Her mood, and she became distressed.

Her manner changed to slightly ruffled,

Her voice then sounded almost muffled,

And she appeared to hesitate

When he had tried to set the date.

Her attitude had been perplexing.

Although at last she did say yes,

The when was anybody’s guess.

Her diffidence to him was vexing –

She seemed at once to dare and daunt –

‘Good Lord,’ he mused, ‘what does she want?!’

XLVII.

Although he wouldn’t have believed it,

She was as dumbfounded as he.

‘To shy from bliss when you’ve achieved it!’

She thought, ‘You’re acting stupidly.’

And though with him I’m empathetic,

To her I’m also sympathetic:

When you yourself have made things worse,

It isn’t any less a curse.

It’s bad enough when others muddle

Things up for you or cause the strife

That discombobulates your life,

But it is worse when you befuddle

Yourself – the onus is the same,

But you yourself must take the blame.

She was as dumbfounded as he.

‘To shy from bliss when you’ve achieved it!’

She thought, ‘You’re acting stupidly.’

And though with him I’m empathetic,

To her I’m also sympathetic:

When you yourself have made things worse,

It isn’t any less a curse.

It’s bad enough when others muddle

Things up for you or cause the strife

That discombobulates your life,

But it is worse when you befuddle

Yourself – the onus is the same,

But you yourself must take the blame.

XLVIII.

And endless futile lacerating

Your self with blaming never solves,

But ends up just exacerbating

The guilt from which self-blame evolves.

And so, my heroine capricious

Would whip her self in circles vicious:

For days she whirled, a spinning top

Until she tumbled to a stop

So dizzied by her self-derision

And nauseated by her pain,

She could not pull the string again

To spin some more in indecision.

She’d had enough of ‘Let it ride,’

Her tailspin ended in ‘Decide!’

Your self with blaming never solves,

But ends up just exacerbating

The guilt from which self-blame evolves.

And so, my heroine capricious

Would whip her self in circles vicious:

For days she whirled, a spinning top

Until she tumbled to a stop

So dizzied by her self-derision

And nauseated by her pain,

She could not pull the string again

To spin some more in indecision.

She’d had enough of ‘Let it ride,’

Her tailspin ended in ‘Decide!’

XLIX.

Thank God. I too am sick of spinning

This dizzy lovers’ tale of mine.

I never thought at Five’s beginning

I’d get to stanza forty-nine;

But that’s the way it is with “wimmin” –

They almost always leave you swimmin’!

(Although, it’s also true with men

One can tread water, now and then).

But now my battle of the sexes –

To use a third stale metaphor

(A practice that I do abhor) –

With all its auguries and hexes,

Its plans and obstacles and frights,

Its feints and joinings and its flights

This dizzy lovers’ tale of mine.

I never thought at Five’s beginning

I’d get to stanza forty-nine;

But that’s the way it is with “wimmin” –

They almost always leave you swimmin’!

(Although, it’s also true with men

One can tread water, now and then).

But now my battle of the sexes –

To use a third stale metaphor

(A practice that I do abhor) –

With all its auguries and hexes,

Its plans and obstacles and frights,

Its feints and joinings and its flights

L.

Has ended, with both parties suing

For peace and future harmony,

And all their wearying, worried wooing

Is bent on conjugality.

Alas, no memory has carried

To me the date when they were married,

But I’m quite sure it could have been

In early spring, nineteen thirteen.

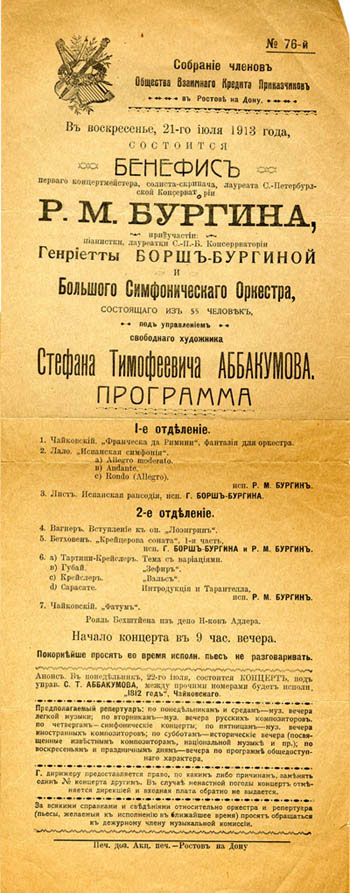

A playbill anchors my insistence:

“July ’13, Rostov-on-Don –

A BENEFIT will be put on

For R.M. BURGIN, with assistance

From Henriette BORSH-BURGINA

And a Full Symphony Orchestra.”[6]Program in Russian. The Benefit took place on Sunday, 21 July 1913. In the First Part, Burgin performed the Lalo Symphony Espagnole and his wife, Borsh-Burgina, the Liszt Spanish Rhapsody. In the Second Part, the couple performed the 1st movement of the Kreutzer Sonata and Burgin did a set of 4 short pieces by Tartini, Hubay, Kreisler and Sarasate.

For peace and future harmony,

And all their wearying, worried wooing

Is bent on conjugality.

Alas, no memory has carried

To me the date when they were married,

But I’m quite sure it could have been

In early spring, nineteen thirteen.

A playbill anchors my insistence:

“July ’13, Rostov-on-Don –

A BENEFIT will be put on

For R.M. BURGIN, with assistance

From Henriette BORSH-BURGINA

And a Full Symphony Orchestra.”[6]Program in Russian. The Benefit took place on Sunday, 21 July 1913. In the First Part, Burgin performed the Lalo Symphony Espagnole and his wife, Borsh-Burgina, the Liszt Spanish Rhapsody. In the Second Part, the couple performed the 1st movement of the Kreutzer Sonata and Burgin did a set of 4 short pieces by Tartini, Hubay, Kreisler and Sarasate.

Copyright © 2019 Diana Lewis Burgin. All Rights Reserved. Please credit when quoting.