There is some evidence to suggest, in the case of At/tempting Room, the dream piece that I shall take up in this chapter, that Tsvetaeva was aware of the oneiromantic impulse behind the poem’s writing. She explained in a letter to Pasternak, written after At/tempting Room was finished (or dreamt), that she intended the piece to be about Pasternak and her while she was writing it, but “it turned out to be a poem about him and me, every line of it!” (quoted in notes to the poem in the Ellis Lak edition of Tsvetaeva’s Sobranie sochinenii v semi tomakh, vol. III, p. 783. All translations of Russian originals are mine [DLB]). Tsvetaeva’s comment on her own poem in her letter to Pasternak of February 9, 1927, is informed by hindsight, of course, and the hindsight afforded by an event whose importance in Tsvetaeva’s creative (and emotional) life cannot be over-emphasized: Rilke’s death on December 29, 1926 (which she had apparently not intuited despite Rilke’s hints in his letters to her, a profound testimony to the fact that the poet’s intuition operated only in the sphere of poetry, not in life or her dealings with real people). After Rilke had died and passed wholly into the reality of sleep, dream, the soul, Tsvetaeva rationalized her quite obvious lack of “human” intuition as an instance, now equally obvious to her, of poetic “insight”. She continues her commentary on At/tempting Room: “A curious exchange took place: the poem was written during a time when I was extremely focused on him [Rilke], but it was directed – consciously and willfully – to you [Pasternak]. And it turned out to be – very little about him – yet about him – right now (after December 29th), i.e. it is a pre-celebration [of his death], i.e. an insight. I was simply telling him, a living person – whom I was setting out to see! – how we did not meet, how we met in another way. That explains the strange lack of love, aloofness, feeling of denial in every line, that upset me my self at the time.” (Ibid., III/783) In this letter, Tsvetaeva stops just short of characterizing her lyrico-narrative “pre-celebration” and “insight” a form of oneiromantic prophecy about her living poet Other and her eternal poet Other/Self.

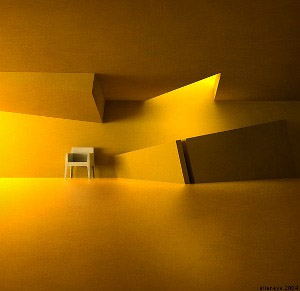

At/tempting Room is divided into four sections that differ from each other in terms of verse form, rhyme scheme and narrative focus. In part one (ll. 1-70), written in alternating quatrains and couplets, the poet attempts to construct lyrically a room seen in a dream where she will meet her addressee, another poet (allegedly Boris Pasternak, or Rainer Maria Rilke, or both simultaneously). She goes on in part two (ll. 71-118), written in quatrains of two types, to describe the room in which she is waiting for her addressee. Basically, it’s an immaterial room of imaginary “planenesses,” designed for a meeting of souls, i.e. an anti/body room where one is protected from the body and other than a body. In part three (ll. 119-150), composed of rhymed couplets, the poet focuses intensively on corridors, viewed both from a child’s and contrasting adult’s perspectives. Finally, in part four (ll. 151-208), which like part one, combines quatrains and couplets, but here, in no particular alternation, the poet first visualizes the corridors of the human body, then, zeroes in on the corridor created by her as a woman, not as a poet, along which she would travel to her lover for a tryst. Since she is not an ordinary woman, however, she will move anti-bodily (spiritually) to her addressee as a light shining at the end of the tunnel of sleep or death. Then, their disembodied, or un-bodied, tryst of minds will take place in the anteroom to paradise, that is, the anti/room, a floorless, wall-less, ceiling-less deconstruction of the room being attempted.

The degree of difficulty Tsvetaeva achieves in At/tempting Room is significantly higher than what the previous two pieces in our set illustrate, and seems to predict the surface incomprehensibility attributed by many readers to it and the works that follow. The only way truly to approach understanding of such hermetic pieces and to render them performable by the reader in the way Tsvetaeva intended them to be played (for more on Tsvetaeva’s theory of reading and writing as performance, see chapter four) is to practice them line by line, stanza by stanza, part by part. Therefore, my reading of At/tempting Room and the last two of the five hard pieces, shall proceed on the principles of explication du texte.

Part one of At/tempting Room is constructed from the repetitions of four substantives, evoked in their insubstantial variants: wall (stena), repeated twelve times; back (spina), repeated seven times, ceiling (potolok) and floor (pol), repeated four times each. These four words conjure very diverse images in the poet’s imagination, from which the material of the room being attempted is made. The four key words emphasize the two main concerns of the poem: the space to be inhabited by two poets (an anti/room) and those poets’ no/body bodies (anti/bodies). From the very beginning of the poem, the poet rejects all physical and material aspects of existence and existing forms or structures. Yet, her non-wall, non-spine, non-ceiling, non-floor, non-room, and non-bodies emphatically do possess form and structure, the form and structure of emptiness. To apply the imagery of part one of At/tempting Room to the poetic (and magical) means by which the poet writes it, one could say that she acts as the corridor that “portered in – […] emptiness’ portable chair.”

The poem begins with the poet’s comment that customarily, a room has always had four walls; at least, this stagnant notion of a room has been the rule up till her attempting one. The fact is, she remembers only three walls in the room she’s attempting, whether because of some glitch, or happenstance, she can’t say. But she can’t vouch for the presence of the fourth wall since a person seated with her back to the wall cannot know for sure whether it exists or not.

The ambiguity inherent in the fourth wall develops into an eighteen-line peroration on one of Tsvetaeva’s favorite paradoxes: the absence of presence and the presence of absence. On one hand, the narrative suggests that clearly, there was no fourth wall because from the direction of that wall, it was “windy”. On the other hand, the poet narrator asks rhetorically, ‘So, what’s in back if not a wall? The answer, “Whatever’s not desired,” again constitutes a play on words, in this case, the common expression, “whatever you desire” (vsyo chto ugodno). The example of “whatever’s not desired” is the telegram from the town of Dno with the news of Nikolai II’s abdication. The undesirability of such a thing makes it seem that it comes from behind, hitting one in the back, as it were, which segues into a metaphysical observation that “urgent wires” come from all directions. More important in the context of immaterialities that the poem describes is the implication that “urgent wires” are often wireless.

Lines thirteen to sixteen return us to the more concrete image of the three-walled room of the poet’s dream, wherein it seems her addressee as a child was sitting, apparently playing the piano with cottony fingers and with his back to the fourth wall, from which the draft blew visibly enough to inflate his shirt into a sail and make the pages of the sonatina he was practising flutter up. The addressee, after all, was only going on nine, the poet adds parenthetically, in order to explain why he was playing a “sonatina,” rather than a grown-up sonata. In lines 17-21, the poet creates a name for the unseen and unprecedented fourth wall. It is “a wall of a back at the piano. Or else at a writing desk, or perhaps a mirror for shaving...” She notes parenthetically the unique way the absent-present fourth wall has “of becoming a corridor in the mirror.” The mention of “corridor” here acts as a foreshadowing of the major theme of parts three and four of the poem. In part one, the corridor constitutes a transformation of the fourth (absent) wall when one looks into a mirror in front of one that reflects what is behind one’s back. The corridor, or the fourth wall’s way of becoming a corridor, is the implied masculine subject of the subject-less masculine past-tense verb in line 23, “perenyos” (portered in). The sense of lines 23 and 24, therefore, seems to be: “It [the fourth wall’s way of becoming a corridor in a mirror] portered in – you glimpsed it – emptiness’s portable chair.”

This “portable chair” into the poet’s imagined room, the poet continues, is the entrance for everyone who can not enter through the door, i.e. the dead. Here there seems to be an allusion to Russian funerary belief, according to which, dead bodies could not be carried through passages used by the living. In the context of the poem, dead bodies are the implied kin of imaginary bodies, i.e. anyone who does not have real (material) soles to their feet, but is (or has an) immaterial soul, instead. The addressee belongs to the unreal, un-bodied category of beings because he, like the speaker, is a poet. Therefore, he “sprouted out of that wall,” or rather, he will sprout out of the fourth wall a paragraph further along in the narrative: He will sprout like Danzas – from behind.

As in dreams so in At/tempting Room one scene segues into another without warning, plan, or even in some cases, logical connective. From a scene of a nine-year-old boy practicing the piano in a windy room, we are suddenly portered in, apparently by the missing fourth wall (a special portable chair-seat), to the historic scene of Danzas’ arrival in Pushkin’s study to tell him it is time to set off for the duel. The comparison of the addressee to Danzas, Alexander Pushkin’s second (and his friend) in the poet’s last duel, is explained in lines 31-35. The addressee-poet will appear like Danzas “from behind” because the fourth wall, ”the latter one,” enters the room not in the manner of an enemy, i.e. “D’Anthèsly”, but in the manner of a poet’s friend, someone who has been “called,” “chosen,” and knows when he is to appear as well as the importance of his presence. (It must be noted here that the “called,” “chosen” nature of the addressee of At/tempting Room makes him similar to the guest-addressee of Air Poem, who appears behind his hostess’s door and waits there patiently as one does who is sure of being awaited and coming on time. Since the addressee of Air Poem is unambiguously Rilke, one can understand Tsvetaeva’s conviction that Rilke in the present, i.e. after death, was really the addressee of At/tempting Room.)

If the poet addressee of At/tempting Room plays a role similar to Danzas, then the poet speaker (Tsvetaeva herself) must be performing Pushkin – a neat instance of the wish-fulfillment aspect of dreams. In the poem, the poet turns his head around to see who has come in, and the arrival asks, “[Are you] all set?” That is the way, the poet concludes, her addressee shall appear in ten stanzas – as indeed he is set up to do in the last stanza of part one, exactly ten stanzas away.

The next section of the poem (lines 37-41) follows logically, if paradoxically, from the scene of Danzas and Pushkin. The poet begins with the general observation that when someone appears from behind one’s back, one senses his gaze like an “eye attack in the rear,” which is obviously something hostile, rather than friendly, more in the manner of D’Anthès than Danzas. Sensing perhaps a contradiction looming, she decides abruptly that she has spoken enough about the “‘in-back’ category” and shifts back to what she was describing before she got into behind-the-backness – that is, the room itself, specifically, now, its ceiling, which, unlike the fourth wall, she is sure existed. She admits, however, that the ceiling was odd – somewhat slanted, oblique,”parlor-like, sort of, possibly, and it slightly droops.” Clearly the “‘in-back’ category” still haunts her, for she compares the downward slant of the ceiling to a bayonet attack in the rear of an army – a sneak attack – an attack in the back from in back that seems to press down on the back of one’s head (the cerebellum). The thought of such pressure and stress brings up another horrifying historical memory, namely, the wall, against which, during the first years of Soviet power, the secret police (CHEKA) lined people up and shot them at dawn: “from behind in the spine.” (line 48) Those executions are the one thing the poet cannot forget or forgive, perhaps because one of the most celebrated victims of them was the poet, Nikolai Gumilev, who was shot on trumped-up charges of counter-revolution in 1921.

The thought of this nightmarish reality makes the poet decide “to leave the walled-in category”. The phrase “walled-in category” obviously parallels the previously used “in-back category” in line 38, but in itself, it requires comment. Insofar as the word “back” is coterminous with “wall” in the first part of the poem, the “walled-in category” of things would seem to equal the “in-back category.” However, the adjective “zastennyi” (walled-in) also can derive from “zastenok” (torture chamber) and the noun “razriad”, which in contemporary Russian means “category,” in the 18th century and earlier, denoted “department” of a specific government ministry: Therefore, “razriad zastennyi” means both “walled-in category” and “torture department” of the CHEKA.

But enough of the torture department! The poet (in her dream, we remember) clearly does not want to go there, as common parlance would put it nowadays. So, she directs her consciousness back to the room that she has not finished describing, and avers that it surely had a ceiling, adding parenthetically and rather provocatively, that she will explain why a ceiling was even necessary; later. Then, she returns to the fourth (absent) wall, “the wall to which, retreating, a turncoat stumbles back,” presumably because that wall is invisible to him as he moves backward.

At this point, the poet is interrupted again, not by herself this time, but by an imaginary interlocutor who asks if there was a floor to her room. She affirms the presence of a floor, but adds immediately that the floor was not for everyone, and goes on to explain why it was not, for the remaining lines of part one. To begin with, the floor was higher than ground level – it was at the height of a swing, a tree-trunk, a horse ready for mounting, a cable on which acrobats perform, and most mysteriously, at the height of the Sabbath. Here, the poet may be thinking specifically of Brocken Mountain where, according to German (Faustian) demonology, witches’ Sabbaths were thought to take place, or she may simply be comparing the height of the floor in her room to the metaphorical height of a, or the Sabbath, i.e. a spiritually lofty height. As it turns out, the floor of the poet’s apparently aerial room is higher than all the actual and metaphorical heights to which she compares it. It is almost as if the floor of this room is higher than the heights of exhilaration, solemnity, derring-do and fantasy, i.e. higher than any literal, or metaphorical height. The floor is at a height that puts the room almost out of this world, almost beyond the gravitational pull of the earth, yet not quite in the world to come. This ambiguous place between earth and the uppermost reaches becomes the favored limbo in which Tsvetaeva’s Pasternak-Rilke pieces are performed.

Being able to ascend to the poet’s room enables the ascender to practise getting used to emptiness without gravity, in preparation for the world that awaits us mortals after death: “Up there we know that we must join heels that are used to gravity with the emptiness” (ll. 59-61). Floors are, the poet reminds us, needed for feet, and human beings are incredibly “rooted” and “en-potted” in life, she exclaims. And a ceiling is needed as protection against the torture of a steady, excruciatingly slow leak. The narrative focus in lines 58-68 keeps switching between the floor and ceiling of the room, which makes them seem interchangeable, though spatially, they are opposites. The apparent interchangeability of ceiling and floor might reflect Tsvetaeva’s knowledge of the common etymology of the Russian words “pol” (floor) and “potolok” (ceiling). The word “potolok” comes from the phrase “po t’lu,” meaning “identical to floor,” where “t’lu” denotes “floor,” “basis,” or “bottom.” At the end of At/tempting Room, the room’s ceiling and floor do change places: the ceiling sinks and floats on water, becoming in effect, the “bottom” of an eternal space, and the floor is replaced by a gap and a shift from floor-level, upwards.

Abruptly, as is her wont, the poet returns to why a floor is necessary for poets (who are emphatically not “en-potted” in life). Besides its use for feet, a floor seals off the base of the room from the ground outside “so grass doesn’t grow into the house” (l. 66) and from the ground underneath, “so soil/earth can’t enter the house in the form of those for whom even a pole (or stake) on a May night is not an obstacle” (ll. 66-68). This category of beings, unstoppable by stakes, refers to vampires and werewolves. As we know from vampire lore, and Nikolai Gogol’s May Night, or the Drowned Woman, even if a vampire has had an aspen stake driven into him, on a certain May night, he, like all vampires, has the capacity to rise from his grave, stalk and prey on the living.

With this final justification of a floor – needed to protect the poets from any threat or pollution from earth – the poet has finished attempting (her) room: It has “three walls, a ceiling and a floor” (l. 70). Into this minimalist mise en scène, the poet commands her addressee to appear.

The poet begins part two of At/tempting Room by wondering how she will hear her addressee’s arrival – will he knock on the shutters? She reviews in her mind several reasons why that way of announcing his arrival seems unlikely: The room has been created in a hurry, it’s no more than “a first draft sketched in pencil on a grey background.” More important, no plasterer (wall-maker) and no roofer (ceiling-maker) built the room – the builder was a dream. And a dream is something immaterial, that maintains only “wireless connections” between people, for example, “a certain man has discovered a certain woman in a dream” (l. 78). Then there’s the virtual non-materiality of the interior: rather than a supplier or furnisher, a dream has outfitted the room, with the result that it is “barer than Baltic-sea sandbars.” The floor is un-waxed, gives off no reflections of ceiling or walls, and reflections are the realities in the dream world of a tempting room. Yet, can one who is used to conventional four-walled rooms really consider this room a room? No, this room is merely a few “planenesses” (ploskosti). A pier looks more inviting than this room created by a dream, which constitutes a mere line-drawing of the sort one might find in the poet’s old geometry textbook that she mastered only recently.

The utter bareness of the room her dream has created causes the poet to question the absence of the one piece of furniture a poet needs, even in an immaterial dream room – a table or desk. In an extremely elusive, elliptically expressed mythological allusion she calls the missing table “Phaeton’s brake,” evoking the myth of Phaeton, the son of Helios, the sun god, who begged, and got his wish to drive the chariot of the sun against his father’s advice and tragically plunged to a fiery death because he lacked the strength to control, or brake, the horses. With the question, “And where is Phaeton’s brake, the desk?” (ll. 87-88), the poet suggests that a table (desk) functions for a poet-creator as a brake ought to have acted for Phaeton. She answers her own question as to the whereabouts of the desk (Phaeton’s brake) with an esoteric statement that initially seems to lack any connection to the context of Phaeton’s fatal ride, due to lack of a brake on his chariot (which, by implication, is his desk): “It’s the elbow nurtures a / desk. Feed the elbowing proclivity [Razloktis’ po sklonnosti], / There’ll be a desk for desk-activity [nastol’nosti].” (ll. 89-90)

I understand Tsvetaeva’s implicit analogy between a desk and Phaeton’s brake on one hand, and “desk-activity” (poetry-writing) and Phaeton’s ride on the other, as follows. Tsvetaeva often uses the notion of elbow movement at a desk to express the process of poetic creation, e.g., in Stairs “Desk is bare – of bagatelles, Desk is elbow-buffered well, Wax is clean, elbow’s whet. Wax is congealed sweat.” (III/129). In the context of the myth of Phaeton, the analog of elbow movement for a poet would be Phaeton’s forearm movement to control the reins and the horses of the sun’s chariot. If Phaeton had had the power of his father, Helios, over the horses, his arms controlling the reins would constitute the necessary brake on the chariot. Tsvetaeva has already established that Phaeton’s brake (his lack of strength) is the missing table in her dream room. But since the table is nurtured by elbow movement, it, and all its table-appurtenances of desk-activity, will appear as soon as she, or any poet, “elbows a lot” to suit his bent.

In other words, the allusion to the myth of Phaeton suggests that Tsvetaeva conceives of the poet as a new, more powerful Phaeton who has the necessary force to control his flight. That force is writing, elbow movement, which governs, refines, polishes his flights of fancy. A poet is Phaeton in control of his brake, which makes him the equal of his father, the sun god. In her mythos of the poet, which Tsvetaeva develops throughout her work, she affirms her equality to the sun. In Air Poem, to take just one example, the poet calls herself a “communicant of the sun” (III/140). Looking back to Astride a Red Steed, one recalls the lyrical etymology of the Tsvetaevan poet’s solar nature – her merging with her Genius who wears the armor of the sun. Just as the poet in Astride a Red Steed had to forsake her earthly, female and lunar self to merge with her solar Genius, so in At/tempting Room, she as Phaeton (the son of the sun god) has to rewrite the conventional myth to become a true child of the Sun, a child in whom “heredity tells” (from the end of Air Poem, III/144). There is a sense in which the Tsvetaevan poet’s epic quest to test, realize and simultaneously overcome her mortal inheritance reminds one of Gilgamesh, the Akkadian hero born two-thirds god and one-third man, whose greatest desire is to overcome the human stain and live forever. One wonders in this connection if Rilke’s great admiration for Gilgamesh was known to Tsvetaeva.

But, to return to At/tempting Room, the reading, like the writing and text of which, leads one through chains of associations that can carry one far a-field from one’s starting point. In reading (or performing) Tsvetaeva’s pieces, one often imitates the poet’s performance in writing them. The idea that making the motions of writing will cause a writing desk to appear in the poet’s dream room, is merely the first of several, magic, “said-done” (skazano-sdelano) capabilities the room possesses. It turns out that just as storks bring children when it is time for them to be born, so any thing will appear in a tempting room when the need for it arises. Therefore, there is no reason to worry or plan ahead of time what will be needed at a rendezvous in this magic room: As soon as a guest arrives, a chair for him will appear, and in general, everything that’s necessary will appear to hand of its own accord. The fact is that this room is located in a very special hotel that facilitates quiet, solitude, and perfect reciprocity for its patrons. The hotel is called “Souls’ Meeting-Place,” which name constitutes a metaphor not of a meeting place, so much as a meeting mode.

The encounter the poet envisions in her room at the Souls’ Meeting-Place Hotel is not any kind of meeting of bodies, but a confluence of souls. Therefore, it is the platonic ideal of meeting, by comparison with which all other concrete meeting places are “for separation,” even the warmest, most intimate ones in the most faraway southern climes. (A souls’ meeting-place is to ordinary meeting places as Mountain in Mountain Poem is to “that mountain,” or as Jacob’s Ladder in Stairs is to the stinking back stairs in a Paris tenement.) Because a souls’ meeting place is an ideal of meeting as well, there is no need for real service personnel. Service is provided by something softer, lighter, cleaner and less obtrusively physical than human hands (servants). Since the poet-guests (the we in the poem) are “touchy people” who are super-fastidious about contact with bodies, they are attended to by the bodiless thoughts, actions and gestures of hands. So, the poet awaits her addressee, without the slightest anxiety as to where he might be, firmly ensconced as she is in “Psyche’s Palace.” While waiting, she begins to ponder the various corridors by means of which her addressee and other people travel to assignations, appointments, and meetings.

Part three and the first half of part four of At/tempting Room are the most opaque and problematic segment of the poem. Their complexity evolves from several factors, all typical of Tsvetaeva. First, the writing is elliptical and chaotic; it moves from one topic or metaphor to another very different one, often with no indication of the connective verbal tissue between them. Second, whatever “meaning” the lines may have, the words and phrases that deliver that “meaning” are in many cases chosen by the poet not for their lexical, but for their sound significance, e.g. lines 135-38. Finally, this part of the poem provides a prime example of what I will argue constitutes Tsvetaeva’s art of the verbal fugue as well as her implied aesthetic belief that poetry is fugue. In parts three and four of At/tempting Room the poet creates a densely contrapuntal, both horizontally and vertically constructed composition on the theme of corridors, into which six discrete corridor “voices” enter, one after the other, to be developed in counterpoint to each other. By “counterpoint” I mean “the technique of combining several thematic lines in such a way that they establish an inter-thematic harmonic relationship while retaining their individuality.” (The Random House Dictionary). The several corridor voices ultimately resolve into a single stream of sound, which is transposed into a visual medium as a unified shaft of light. Light is an anti-corridor “corridor” that seems to signify the ultimate fugue, in both the musical and psychopathological senses of the term, the flight from separate voices and material reality.

The first corridor voice enters in line 120, singing of wind (an airway), passing through (a pathway), and the existence of corridors as the poet’s single conviction as to what exists on the way to her room: “Corridors – the one thing I’m sure of.” Eight lines later, the second voice sounds, affirming corridors as “the taming of distance.” The third corridor voice comes in two variants, or phrases, separated from each other by a line: Variant one: “Corridors: canals of houses” (l. 142); and variant two: “Corridors: the inflows of houses” (l. 144). This third voice develops the theme of passage ways by introducing “hallways” and “entryways.” Voices four (l. 151) and five (l. 159) effect a major shift in the site of the corridors that are being sounded, a horizontal shift from a building’s corridors to the human body’s, “corridors,” that is, its arteries, veins and nerves. The implication of this metonymic shift (a shift by contiguity) is that the places human beings move into, out from, and through replicate the place they inhabit, bio-physically. Both of the body’s corridor systems are then compared to the railroad networks human bodies have created in order to transport themselves from place to place over long distances. Railroad networks include both the network of tracks spreading out from the main junction (this parallels the network of veins and arteries that circulates blood to and from the heart), and the network of signals conducted through wires from the main railway switching station (analogized by the nerves that conduct impulses from the brain to the different parts of the human body). Finally, in line 167 the sixth corridor voice enters in direct counterpoint to the third voice. The sixth voice also sings of houses; but unlike the third voice, it deals with the subways that run under buildings rather than the ground-ways in and out of houses: “Corridors: the tunnels of houses” (l. 180) and “Corridors: the fissures of houses” (l. 182).

The point of Tsvetaeva’s elaborate, six-part corridor fugue seems to be the poet’s in-depth meditation on “means of movement,” ways of fleeing, of moving to, through, around, under, above. The six corridor voices include airways, passageways, hallways, canal-ways, river-ways, entryways, railways, subways, and so on. In addition to these generalized plural “ways,” there is one singular, specific and personal way which the poet has created, and it can be called my way.

Having given an overview of the six-part corridor fugue, I shall now attempt a close reading of the verbal counterpoint it creates. We left the poet at the end of part two as she patiently awaits her addressee in the palace of Psyche. She comments at the beginning of part three that “Wind alone is dear to a poet.” Hence, her certainty in the presence of corridors leading to the Souls’ Meeting-Place Hotel, for corridors are the means by which wind is created. Movement from one place to another, the idea of “passing through” or “being on the march” is the essential principle governing the existence of armies and poets, for like a soldier, a poet must march a long way to achieve realization of his goal, which is, to appear suddenly in the middle of a room, looking like the lyre-bearer god, Apollo.

While poets are in the process of writing poems, they are like soldiers on the march, treading long corridors on the way to a stopping place. Their incessant marching raises “wind, wind topping [their] brows.” “Wind topping the brow” appears to be a metaphor for struggle, resistance, Beethoven-like “going against the tide,” which Tsvetaeva often notes in her writing was the governing principle of her mother’s life, and became her own. The wind of resistance that is raised by creative labor is like the wind raised by the banner of a troop of soldiers. The elliptically expressed comparison in lines 125-26 contains an important inversion, however: the banner is not put in motion by the wind, but it creates wind, in the same way as the footfalls of the poet do. In other words, creativity or thought puts nature in motion, or even drives nature (wind). The statement of this aesthetic credo constitutes the full development of the first corridor voice, at which point the second voice enters.

The elliptical line 127, “For ‘and-so-forth’s’ usual framing–,” if fleshed out, might read: “corridors are the place where the abstract idea of ‘and so forth’ is en-framed.” This line prepares the way, via a sound identity between its last word, “dale” (forth) and the genitive noun form “dali” (distance’s), for the statement of the second fugal voice: “Corridors: the distance’s taming” (l. 128). Corridors tame distance, because they make it housebound and approachable, reducing “distance” to a human scale. The idea of the taming of distance evokes a reminiscence of childhood from the poet that constitutes the development of the second corridor voice. Tamed distance conjures up the figure of a “bonna” (governess, nanny) (l. 138), a foreigner whose “rook’s face” has a decidedly non-Russian look. The “nanny” in At/tempting Room seems to be a lyrical evocation of Tsvetaeva’s real-life “German-nanny Augusta Ivanovna” whom the poet recalls in one of her notebooks (Svodnye tetradi, p. 38) and in her autobiographical prose works. In the poem, the distance becomes the nanny, who moves with a measured stride appropriate to following the small footsteps of children in order not to get ahead of them. It (Distance/Nanny) is wearing a slicker (waterproof) lightly sprinkled with raindrops. The sound of the phrase, “in a slicker” (v prufe), a foreign word in Russian, calls to the poet’s ear various other childhood-related words of foreign origin that imperfectly rhyme with it: “grifel’” – pencil (redolent of the schoolroom), “tufel’” – slipper (suggesting the bedroom), “kafel’” – tile (evoking the bath and the kitchen). These words lead the poet to recall, via sound association, the Eiffel Tower which in childhood, seemed somewhere very distant and exotic, clothed in a train of multicolored lights, a “slightly peacockish” train.

The final segment of the poet’s remembrance of her childhood focuses on the special qualities of a child’s perception, which are a major component of the adult poet’s view of the world. For a child, as the poet says in line 135, everything is concretized and essentially metonymic: in the part, a child sees the whole. A pebble (gal’ka) on the shore or bottom of a river represents for the child the river from which she picked it up. Similarly, the child sees only a “smitch” (dol’ka) of the whole distance; distance (dal’) is not visible to the child – rather, she sees a “distance-sliver” (dal’ka): “Since for a child a pebble’s a river, / smitch of distance, a distance-sliver” (ll. 135-36). Tsvetaeva continues her musical indulgence in “distance” and brings the second voice to its climax: “In a child’s limited memory cranny, distance with hand baggage, a nanny… Who didn’t tell us (distance was modish) what in the luggage we were toting…” (ll. 137-39).

There is absolutely nothing driving the above mentioned lines other than sound, yet they do manage to convey some sort of sense and even, miraculously, an underlying thought on the meaning of life. In a child’s limited (“bottomed,” i.e. having a bottom) but resonant memory, distance will always remain a nanny with hand baggage, a nanny who didn’t blab about things children don’t need to know, such as what is precisely in the baggage carts following them to their destination. It was the fashion at the time of the poet’s childhood to keep adult information distant from children. Distance becomes a metaphor of what lies ahead on life’s road: in childhood, children were not vouchsafed details of what they were carrying with them and what awaited them at the end of their journey, whereas adults know only too well what baggage they drag along with them – if only from childhood! – what misfortunes pursue them as they move on in life.

The implied notion of misfortunes that pursue one in life prepares the way for the entrance of the third corridor voice that will sound in sharp contrast to the optimistic second voice of childhood perceptions: that third voice, seemingly connected with childhood through the image of the “pencil box” that describes its size, “a distance of pencil box size,” paradoxically (by contradiction) evokes different, adult corridors, “the canals of houses,” “the inflows of houses.” Unlike the corridors of childhood that were self-contained within the house, or in parts of the house, these more ominous corridors lead in and out of houses and buildings, leaving the inhabitants “open” to the outside world. As canals are to a river that courses through a city, or as inflows (tributaries) are to the river flowing through a region or territory of a country, so corridors are to municipal buildings (we have left the safe haven of home and gone off to workplaces and offices), both ways of moving around inside them and moving into them. Along such corridors events, deadlines, weddings and fates pour into buildings, both public and private. And these events, times and fates of people’s lives and deaths are often put in motion by written documents, signed by the pens in the pencil box mentioned in line 141. In the childhood world, pencil boxes were innocent enough, however; now, in the outside world of adults, a pencil box acquires far more serious, do-or-die significance. It holds the instrument, a pencil or pen, the stroke of which may determine the distance toward which one will be heading in life. All depends on what the pen signs – a contract, a wedding license, or a denunciation.

Lines 145-50, which conclude part three of At/tempting Room, develop the frightening idea of corridors as the official channels through which denunciations travel, determining the fates of people. At five in the morning, brooms are not the only sweepers of the corridors of public buildings. People with written denunciations sweep through them, too. The “nameless informing” or literally, anonymous letter mentioned in line 145 has specific Russian historical connotations. Such anonymous letters containing slander and denunciations were slipped under doors during the terrors of Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and later, Lenin and Stalin. The stated “podmetnoe” (anonymous) letter seems to echo mentally, in the reader’s inner ear, with the unstated “podmetyonnoe” (swept up) letter, so that a double entendre is suggested. This merely implied auditory word play on the words podmetnoe/podmetennoe controls the imagery in this section of the poem. Brooms (metly) sweep up old letters and papers in the corridors while denouncers sweep down the same corridors with anonymous letters.

Because of the implied double meaning of sweeping corridors (i.e., corridors being swept and corridors turned into conduits for sweepers (denouncers and janitors)), the corridors have two odors: they smell of caraway seed, a non-threatening early-morning smell of freshly baked rolls, and of turf, an ominous early-morning smell of freshly dug graves. And should one ask the corridor-sweeper what his line of work is, he will reply, “Cor-ri-dor work,” articulating each syllable, as was typical of a Soviet-Russian military man or CHEKA operative. In pre-revolutionary Russia, moreover, the servant in charge of sweeping all the rooms on a hotel corridor was called a “corridor lackey.” The question, “Your occupation?” appears on official questionnaires in pre-revolutionary and soviet times; in both eras, corridor lackeys were often police informers. This is one very good reason why the Souls’ Meeting-Place Hotel does not need service personnel and why poets are such touchy guests.

At/tempting Room appears to contain more than one allusion to the tragic fate of Nikolai Gumilev, the poet-contemporary of Tsvetaeva’s who, as noted earlier, was executed by the CHEKA in 1921. Tsvetaeva, like most of the intelligentsia, never got over Gumilev’s death. As a poet and martyr to the Revolution, as one of the innocent; denounced victims of early-morning shootings, Gumilev is constantly on the poet’s political mind in At/tempting Room, a prime example in real life why poets must escape from death and this world, according to Tsvetaeva.

The last two lines of the second part of the poem serve to realize the revolutionary theme implied in the development of the third corridor voice: Corridors as the “canals” and “inflows” of buildings, manned by those who do “corridor work” in two senses of the word, the literal and positive – i.e. cleaning – and the metaphoric and negative – i.e. purging. Those who do corridor work in the latter sense, do it in order to effect a new Carmagnole, i.e. French Revolution, “which threshes [heads] by means of corridors”: “Merely demanding the French Revolution’s / corridors-wise threshing solutions!” (ll. 149-50). The adverbial means of action, “corridors-wise” in the context of the third corridor voice denotes “by means of anonymous letters,” which, in the context of the French Revolution, signifies denunciations that led to beheadings. In traditional imagery, executions are represented as “harvests of heads”. This is the implied underlying conventional metaphor of the alliterative phrase, “The Carmagnole threshed”. At this point, the six-part corridor fugue has reached the climax of its development and transitions into the fourth and last part of the poem, where the last three voices will enter and be worked out, in turn.

For voices four and five, the poet shifts to a new corridor site, the human body, developing the notion of corridors to metaphorize the circulatory system of veins and arteries and then, the system of nerves. Both of these bodily corridor systems are compared to the networks of railroads that crisscross a country. In the treatment of the corridors of the human body, the poet makes an important distinction between corridors in general, and one (this) corridor in particular: “Whoever constructed corridors” versus “This corridor’s made by / me…” In these two phrases, not only is the plural juxtaposed to the singular, but case and voice are contrasted as well. The plural “corridors” is in the accusative case in an active sentence while “this corridor” is in the nominative case in a passive sentence with the poet-creator as agent in the instrumental. The unnamed creator of the body’s circulatory (and nervous) systems appears to be God. He is the one who knew just how to turn the veins and arteries, so that blood would corner the heart gradually since the angle of the heart is acute.

Like a magnet, the heart attracts thunder and storms and if the blood flows too fast, the heart can rupture. This complex elliptically expressed image of the circulation of blood to and from the heart has both literal and metaphoric significance. On one hand, a well-functioning circulatory system in physiological terms insures that blood flow around, into, and out of the heart is steady and continuous; expressed in the language of the poem, “The island of the heart should be carefully washed by blood from all sides.” On the other hand, the idea of a slow and steady flow as opposed to a sudden rush of blood to the heart has metaphoric suggestiveness. We recall that the poet is anticipating her meeting with her addressee in Hotel Souls’ Meeting-Place. She awaits him calmly at the end of part two, and so here, when she takes up her story again at the beginning of part four, she implies that she does not want the meeting to be an emotional storm for her heart, a high-voltage experience that might cause a heart attack. Just as the Creator of the human body built its blood vessels to insure a steady, continuous flow of blood around the heart, so “this corridor” has been created by her “to give the brain the time it needs to let the whole body know, all along the line,” about the meeting of poets (ll. 160-63). The noun “line” is used in three different meanings at once as three different images to which it is central are almost superimposed one on the other. “Line” (линия) denotes the network of nerves, the network of blood vessels and a railroad line.

The idea of a railroad line is worked out in most detail in the poet’s narrative as she continues exploring what it means to let a whole system know all along the line: “To make known all along / the line: from ‘end of boarding’ to the junction of heart.” Suddenly, a train is seen approaching the junction, “‘Train’s coming!’” and the scene, equally suddenly, acquires a morbid new direction: “To end it – / shut your eyes and jump! / To not – away / from the rails.” (ll. 165-67). Suicide seems always to hover, temptingly, on the rim of Tsvetaeva’s consciousness. Although the allusion in the lines just quoted to Anna Karenina, specifically to the heroine’s suicide may seem tonally out of keeping with the mood of joyful anticipation of a meeting of poets’ souls, it is possible that the poet wants to suggest that some form of death (as it happens, the exact opposite of Anna’s violent death) must precede a meeting of souls, or that the moment has come to make a choice between the poet’s native spiritual life or his false mundane or physical life. By emphasizing the not in the elliptical line, “To not – away / from the rails,” the poet suggests that the choice not to end life, is somehow negative – it is better to shut one’s eyes and jump!

The poet reiterates that the corridor to her room is created not by the poet in her, but by the woman in her. That’s the part of her that lives in the physical world where it is necessary to give one’s brain time to prepare for a rendezvous. A meeting implies a place, even a definite locale (though her “room” is nothing but “planenesses”). In preparing to meet her soul-mate, a real woman needs a corridor to move along while she plans, calculates, rehearses what she’ll say, how she’ll move and look. Doesn’t a flesh-and-blood woman on her way to a tryst want everything about her (me) to be perfect for her (my) lover (you)? asks the poet rhetorically in lines 171-74 as she gives the meeting of her and her addressee’s souls the suggestion of a lovers’ tryst without that ordinary, earthly rendezvous’ materiality and sexuality: “So love is creaseless – / wholly, so I can wow / you, to the final creasing – / Of lips? Or my dress?” The poet, however, is only part “ordinary woman,” and the room she has envisioned for her rendezvous is emphatically not a conventional room as we have known from stanza one. Therefore, while traversing the corridor she has created, the poet won’t be straightening her dress or smoothing her lipstick, but she’ll be smoothing her brow in order to insure a perfect marriage of minds with her poet-addressee. As she quips in line 179, “All women can straighten their dresses!” What’s more, ordinary “corridors: are the tunnels of houses” (l. 180).

With this statement redefining ordinary corridors, Tsvetaeva introduces the sixth voice of her fugue, echoing the third voice, which also spoke of corridors as passageways in houses. It is important to note that the passageways to which the corridors of houses are compared are all subterranean, all dug out of the ground: canals, inflows, tunnels, fissures. Ordinary, earthly corridors are under or through the earth, but the corridor created by the poet is of, and for light and for traveling above the earth. Ultimately, the corridors of houses and of materiality are to resolve into the corridor of light and immateriality that is the poet herself (in un-bodied form). This finale of the corridor fugue, the flowing of the six voices (earthly corridors) into the light at their end, occurs in lines 181-88:

These eight lines are built on the binary contrast between darkness and light, blindness and sightedness, and underground tunnels and the outside air/light, all of which are implied in the allusion in line 181 to Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, namely “the old man [blind Oedipus] led by his daughter and sister [Antigone].” Tsvetaeva seems to be saying that corridors as the fissures and tunnels of houses behave like the old blind Oedipus who moves along into a blind, seeing nothing, led by Antigone, his eyes.

Directly addressing her fellow poet after painting this sorry picture, the poet urges him to take a look at the lyrical scene she has been composing. In her immaterial creation, she herself, as in a letter, or the dream she started out describing at the beginning of the poem, will come at him as a shaft of light, or, even more ephemerally, as his premonition of the light to come after he closes his lids (i.e. falls asleep or dies). In other words, the poet visualizes herself as her own unique corridor as well as the goal of her addressee’s blind passage through sleep or death to the life of a new dawn or of the soul.

Death has been ever-present in this poem, from Pushkin’s fatal duel, to the dawn shootings of the CHEKA, to Phaeton’s plunge to earth, to the guillotine’s harvest of heads, to Anna Karenina’s suicide. In line 187, the death motif is implied in the phrase, “the last light-point you descry,” i.e. the moment just before death or final sleep. In this moment, the poet will appear as her addressee’s light, leading him via herself (her corridor) to their souls’ rendezvous. There is a lot of implied, typically Tsvetaevan non-physical eroticism here. Unlike Anna Karenina, for whom the light in her eyes and of her soul went out forever when her consciousness flickered “at the last light-point,” the poet’s addressee shall, at the end of his dark tunnel of sleep or earthly life see the light that is she – “I – a luminescent eye.” (The phrase “luminescent eye” (световое око) can’t help but call to mind the title of Tsvetaeva’s rave review of Pasternak’s collection, My Sister Life, which she entitled “Luminescent Downpour” (Svetovoi liven’).)

After the six-part fugue comes the finale of the poem, a kind of “In paradiso,” sung by a soprano choir of angels – I hear it as the final part of Fauré’s “Requiem.” Lines 189-208 take place in the “afterwards,” or afterlife, construed not as a specific religious afterlife but as the super-earthly real and eternal life of poets, where the constraints of materiality are gone. It is for this eternal life that, Tsvetaeva later argued in My Pushkin, Pushkin had to die in his duel, which was recalled in part one of At/tempting Room. The best way to describe the afterwards, the poet notes elliptically in line 190, is to say it is in tune with a (or the) dream. First, “he” will have ascended, then, their brows will have bended to one another, his having jutted out, in a spiritual reenactment of the crude, merely sexual, meeting of mouths in a kiss.

Once the marriage of the two poets’ minds/souls is consummated, their need for any materiality vanishes. Thus, in the last thirteen lines of the poem, the attempted room constructed, if only minimally, in the poem, collapses and deconstructs – it turns out to be an anti-room (anteroom to paradise). (We note, perhaps needlessly, that the intransitive verb “pytatsia” (to attempt), often connotes “to attempt unsuccessfully.” Etymologically, the transitive verb “pytat’” (to try, torment) is related to the Latin verb putare, to speculate, suggest, think, weigh and judge. Many of these forms of cogitation are implied in Tsvetaeva’s attempting a room.) The three walls disappear first, which causes the ceiling, once merely slanted, to list severely like a sinking ship. The sinking of the ceiling is interrupted by the poet’s noting the disappearance of language, i.e. the need for language, as the disembodied poets’ mouths communicate wholly in vocative “O’s,” – visually the shape of the letter O depicts a void, a nullity. “The floor is surely a gap,” the ceiling floats (the water it was designed to keep out now is beneath it). The floor with its rubbish that seemed never to have had any function except to require sweeping has apparently “dropped dead,” at the poet’s command. No more corridor sweepings or denunciations! This liberates the poet to “look up” from the dirty floors she’s had enough of in real life and realize her poet-self since “a poet is no more than a dash” (the sign of punctuation – that can signify a pause in the train of thought). The poets’ bodies having become nothing or no/bodies, the floating ceiling dematerializes into “all the angels singing…” sound that has no upper limit and goes on forever…